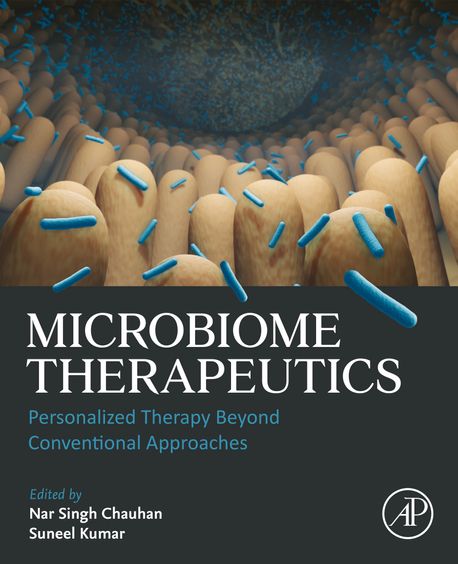

Importance of Microbiome based Therapeutics:

In the last decade, the human microbiome has emerged from scientific obscurity to become a central focus in discussions around chronic disease, immunity, and even mental health. While the general public associates the microbiome with probiotics and gut health, clinicians and researchers now view it as a complex, dynamic therapeutic target. With over 39 trillion microbial cells inhabiting the human body outnumbering human cells the microbiome is no longer a side character in medicine; it is a key regulator of human physiology.

1. Understanding the Microbiome: Beyond Gut Flora

Most discussions about the microbiome focus narrowly on the gastrointestinal tract. However, the human microbiome includes microbial communities residing on the skin, in the oral cavity, lungs, urogenital tract, and even within the placenta and tumors. Each of these microbiomes interacts uniquely with its local environment, producing metabolites, modulating the immune system, and influencing gene expression.

Notably:

- The gut-brain axis connects intestinal microbes to mental health.

- The skin microbiome can influence inflammatory disorders like eczema and psoriasis.

- The lung microbiome is being implicated in diseases like asthma and COPD.

This broader view positions the microbiome as an organ system in its own right, one that is modifiable, measurable, and increasingly targetable.

2. Probiotics: A Simplified Solution to a Complex Problem

Probiotics are often marketed as the go-to solution for “restoring gut health.” However, most commercial probiotics contain only a handful of strains — primarily Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium — and may not survive gastric acid or colonize the gut long-term.

Furthermore, microbiome diversity, not just abundance of “good bacteria,” is more strongly associated with health outcomes. Blanket probiotic use may even be counterproductive in some cases — such as after antibiotics, where probiotics can delay natural microbial reconstitution.

This has prompted researchers to pursue targeted, next-generation therapies that move far beyond generalized supplementation.

3. Next-Generation Therapies: The Future of Microbiome Modulation

🔬 Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT)

Initially used for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection, FMT has shown efficacy rates >90% in this context. Researchers are now exploring FMT for:

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

- Autism spectrum disorders (ASD)

- Cancer immunotherapy responsiveness

The challenge? Standardizing the content, safety, and delivery of FMT remains complex, and its regulatory classification (drug vs. tissue) is still under debate.

🧬 Microbial Metabolites as Drugs

Compounds like butyrate, indole-3-propionic acid, and trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) are microbial byproducts that directly influence inflammation, metabolism, and cardiovascular risk. Drugs that modulate the production or absorption of these compounds are being developed as a form of indirect microbial therapy.

🦠 Synthetic Biology & Designer Microbes

Using CRISPR and synthetic biology, scientists are engineering bacteria to:

- Detect and kill tumor cells

- Secrete anti-inflammatory compounds

- Act as biosensors for gastrointestinal bleeding

These microbes function like “smart pills,” offering real-time therapeutic action inside the host.

4. Microbiome and Precision Medicine

Every individual’s microbiome is unique — influenced by genetics, diet, geography, and early-life exposures. This makes the microbiome a personalized therapeutic marker.

In oncology, for instance:

- Patients with higher microbiome diversity have better responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors (e.g., anti-PD-1 therapies).

- Manipulating gut microbes may enhance chemotherapy effectiveness and reduce toxicity.

Microbiome profiling could soon become as routine as genotyping in tailoring treatments.

5. Ethical and Clinical Challenges

- Regulatory ambiguity: Are microbiome therapies drugs, transplants, or something new?

- Standardization: No two FMTs are alike; donor variation is significant.

- Unintended consequences: Could altering the microbiome trigger autoimmune disease or metabolic imbalance?

As clinicians, we must approach microbiome modulation with the same rigor we apply to traditional pharmacology demanding robust trials, long-term data, and ethical oversight.

Conclusion: A New Frontier in Therapeutics

The future of medicine lies not only in targeting human cells, but also in co-managing the ecosystems within us. The microbiome is not just a buzzword or a wellness fad it is a therapeutic landscape rich with possibility.

As future physicians, we must move beyond the surface-level understanding of “gut health” and engage with this field through research, clinical innovation, and patient education. Because in targeting the microbiome, we’re not just changing bacteria — we’re transforming the very foundations of health and disease.